#043 An Architectural Approach to Level Design - Chapter 4 - Basic Gamespaces

Architecture is the thoughtful making of space. —LOUIS KAHN

- will look at some simple spatial principles from architectural design.

- will explore historic gamespaces such as the maze and labyrinth, learning how these ancient space types influence modern game structures.

- will explore other popular spatial types found in modern games and discover how they are used to enforce different gameplay mechanics.

- will consider player point of view and discover what advantages and disadvantages are found in first, third, and other camera views.

ARCHITECTURAL SPATIAL ARRANGEMENTS

Games and architecture differ in the fact that real-world architecture must conform to real-world rules.

With these differences in mind, spatial designers for games can take advantage of architectural lessons within the freedom of game design environments.

Figure-Ground

Figure–ground is derived from artistic notions of the positive and negative space of a composition, where positive space describes the area inhabited by the subject of a piece and negative space describes space outside of or in-between subjects.

Figure–ground theory in architecture comes from the arrangement of positive space figures, often pochéd building masses, within a negative space ground.

According to architectural designer Matthew Frederick, spaces formed by arranged figures become positive space in their own right, since they now have a form just as the figures do.

From an urban design standpoint, these framed spaces are often squares, courtyards, parks, nodes, and other meeting areas where people can “dwell,” while remaining negative spaces are for people to move through.

When utilizing figure–ground, both figural elements and spaces can be implied, either by:

- demarcating a space with structural elements;

- creating negative spaces that resemble the form of nearby figures.

Gamespaces are often based on mechanics of movement through negative space, using positive elements such as ledges or supports for a player’s journey.

Designers can communicate with players via implied boundaries or highlighted spaces that use figure–ground articulations.

Form-Void

Form–void (also called solid–void) is in many ways a three-dimensional evolution of figure–ground.

Just as figure–ground is spatial arrangement by marking off spaces with massive elements, form–void is spatial arrangement by adding masses or subtracting spaces from them.

Arrivals

Based on what we have seen in figure–ground and form–void, level design is an art of contrasts. It is also an art of sight lines, pathways, dramatic lead-ups, and ambiguity about the nature of where you are going. All of these elements contribute to the experience of an arrival, the way in which you come into a space for the first time.

Much of how we will communicate with the player is through arrivals in space. It is also through arrivals that a space ushers players toward their next destination or allows them to choose their own path.

Much of how you experience a space when you arrive in it comes from the spatial conditions of the spaces that preceded it: if you are arriving in a big space, the spaces leading up to it should be enclosed so the new space seems even bigger.

Another important element of how players arrive at spaces is their point of view from the arrival point.

When a player looks through a doorway their ability to plan their next steps has a lot to do with how well they can “read” the space they’ve just arrived in.

Controlling the information shown in a view is very important and if done well, can make a more satisfying experience.

Genius Loci

Genius loci, also known as spirit of place.

Roman believed that spirits would protect towns or other populated areas, acting as the town’s genius.

Latetwentieth-century architects adopted the phrase to describe the identifying qualities or emotional experience of a place. Some call designing to the concept of genius loci placemaking, that is, creating memorable or unique experiences in a designed space.

Beyond individual gameplay encounters, level designers can implant genius loci within the entirety of their gamespaces and use it as a tool for moving players from one point to another.

Genius loci can be built through manipulations in lighting, shadows, spatial organization, and the size of spaces…

Cyan Han: elements should follow and contribute to the level’s experience.

Spaces in a game with little or no genius loci can be circulation spaces, that is, spaces for the player to move through to get to the next destination.

Depending on the gameplay you are creating, circulation spaces may be a chance to rest between intensive encounters or tools for building suspense before a player gets to the next memorable gameplay moment.

HISTORIC GAMESPACE STRUCTURES

Beyond defining a specific spatial condition of a game environment, these classic spaces serve as important models for how game worlds can be structured: in linear, branching, or interconnected ways.

Labyrinth

Classic labyrinths are unicursal—consisting of a single winding path.

Labyrinths also demonstrate that even in linear gamespaces, both literal and gameplay twists, turns, and challenges can add interest to an otherwise straightforward pathway.

As Salen and Zimmerman point out, games are often the least productive way to accomplish a task.

Such a structure is useful for games where an embedded narrative, theme, or argument is being communicated to the player.

Maze

Mazes are said to be multicursal, having more than one defined path, unlike unicursal labyrinths.

From the Renaissance through the nineteenth century, architects also developed hedge mazes, multicursal pathways through tall bushes in the gardens of large estates. Originally unicursal labyrinths, these structures evolved into branching paths that often contained several points of interest

The branching nature with potential dead ends implies a rich risk–reward structure, where the game asks you to weigh different uncertain options with the hope of choosing an advantageous answer.

The dead ends in mazes do not always have to be negative. Games with even simpler worlds can also utilize small branching paths.

Rhizome

A term from botany, rhizomes are networks of roots formed by underground stems of plants.

As a philosophical concept, rhizomes describe a lateral representative structure of information and data without distinctive entry and exit points.

The most important of the guidelines of a rhizome is that every point in them is connected to every other point at the same time.

Spatially, the term rhizome can apply to any place that can be instantly traveled to from any other place.

Instant transportation.

SPATIAL SIZE TYPES

Size distinctions for gamespaces create some very interesting emotional scenes in game levels.

Narrow Space

Narrow gamespace is that which is not much larger than a player character’s own size metrics—often with space for only two of such a character to stand in a passageway.

Narrow spaces create tension by giving space scarcity, limited amounts such that space itself becomes a valuable resource.

Evoking vulnerability by limiting player movement options in horror games.

Narrow spaces in stealth games offer concealment from enemies, but at the cost of both mobility and visibility.

Intimate Space

Intimate spaces are neither confining nor overly large and are, in fact, what one might call metric appropriate, at a size that comfortably supports the size and movement metrics of player characters.

In some games, the amount of space described in this way may change if the abilities of player characters can expand through additions such as high-jump capabilities or others.

Multiplayer:

- Create a spatially even playing field.

- Contrasting narrow and intimate spaces creates interesting gameplay situations and allows players to build strategies of how to proceed.

Single-player:

- friendly space

- give players an advantage over foes

Batman: Arkham: player is stronger than foes.

Prospect Space

Wandering through a large open space and open to attack.

Multiplayer: a spatial advantage over another / vulnerability (deathmatch map) Single-player: boss rooms / makes the player’s own movement metrics seem agonizingly slow. (the contrast in movement metrics)

Prospect spaces are similar to narrow spaces in their potential for creating fear in the player.

- Narrow space: claustrophobia

- Prospect space: agoraphobia

MOLECULE LEVEL SPACES

How to link these spaces together in interesting and meaningful ways Based on interpretations of mathematical graphing theory - molecule design

This chapter discusses the basics of molecule design and enhance it by combining its functionality with proximity diagrams.

The Basics of Molecule Design

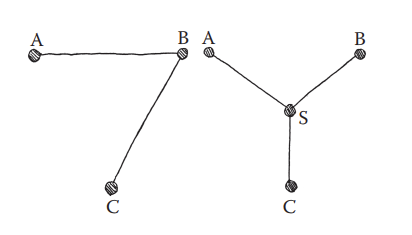

Molecule design is primarily focused on the relationship between play spaces, treated in the graphs as nodes and edges.

Nodes are the play spaces themselves—areas with significant enemy encounters, item pickups, spawn points, or opportunities for action.

Edges describe the relationship between these spaces, visual or spatial (as in you can travel from one to another).

In proximity diagrams, the size and importance of spaces are described by the size of bubbles used to represent those spaces. The bubbles are connected with lines of varying thickness to show how important it is for spaces to be connected.

Dotted lines show that spaces are viewable from one another, and solid lines show that you can move from one to another. Arrows on the solid lines show if spaces are one way, and thick lines show that spaces between the nodes are direct paths.

A description of how spaces interact with one another.

Steiner points

This diagram shows the Steiner tree puzzle and the answer utilizing a Steiner point.

This diagram shows the Steiner tree puzzle and the answer utilizing a Steiner point.

Steiner points are essentially shortcuts in level paths.

- jumping from high ledges onto lower ones to save time

- incentivized with power-ups or other rare items

Spatial Types as Molecule Nodes and Edges

Nodes are opportunities to emphasize the gameplay mechanics and genius loci of your level.

Nodes can contain their own smaller maze spaces.

The circulation spaces that bring players from one node to another may be very linear, as may the nodes themselves.

Molecule diagrams may also describe spaces where spatial size changes significantly.

- Multiplayer: spawn area - intimate space, battle area - prospect space

- Single-player: transation from intimate / narrow space to prospect space create “Jesus Christ spot”.

Steiner point can be used as an obstacle:

- Player has to jump through top of the pillars, closer way (steiner point) may cause falling to startpoint.

- if returning, steiner point becomes a shortcut again.

wtf are you writing about

HUB SPACES

hub-and-spoke spaces

Hubs are a type of intimate space that behaves like a lobby where the player may access a game’s different levels (the spokes). Usually non-threatening and offer players the ability to explore within the metrics of their character’s abilities.

Performance standpoint: for loading levels in an efficient way. Gameplay standpoint: structured around collecting resources; offer freedom for players to choose what missions to take.

In many ways, hubs offer the best of both linear and open styles of gameplay.

SANDBOX GAMESPACES

Sandbox worlds are named for their ability to have defined boundaries while also allowing players to play however they want in less structured ways than many other games allow.

- Single-player: whether to follow a story or simply wander

- Multiplayer: battle royale

Problems: user orientation & location awareness.

This section is for urban design principles that can be used to build successful sandbox spaces.

Pathfinding with Architectural Weenies

Architectural weenie: landmarks used to attract players to goal points in games.

Allow these worlds to retain their openness but still direct players toward places that designers want them to go.

Half-Life 2: use building’s color to guide players.

Some games use weenies as high points so players can see large areas of the world from them.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild No Man’s Sky: valuable resources located on hilltops

Multi-functions:

- directing player action

- helping players better navigate gamespaces

Organizing the Sandbox: Kevin Lynch’s Image of the City

finding one’s way in a large open space

The Image of the City: how people form mental maps of cities with these elements: landmarks, paths, nodes, districts, and boundaries.

Landmarks

Landmarks are recognizable elements that can be guideposts to people in an urban space. Same as weenies.

Functions:

- call attention

- allow players to orient themselves by observing their relationship to the landmark in space

- track progress by measuring proximity to landmarks

Half-life 2: the final target - Citadel tower, is visible from most of levels, players can track their progress by observing how close they are to the structure.

Paths

Paths in urban design include roads, sidewalks, and other thoroughfares that allow people to travel through the city.

Paths can have their own challenges, but are often intimately scaled spaces without significant aesthetic features.

Functions: usher players through to the next point

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim: open landscapes. Paths are less direct, players can enact their own Steiner points. To mitigate the risk of getting lost, they use subtle geographic features such as dirt paths, signposts, rivers.

Nodes

The intersections of pathways offer a variety of opportunities for engaging users. They can be guide points for navigation, also places for people to gather or interact.

Functions:

- locations for landmarks to reside, channeling different paths onto one end goal.

- strategic decision points: observers can decide what path to take next.

Open-world games: such decision nodes are everywhere, forcing players to prioritize how they wish to spend their time.

Edges

Edges are boundaries not formed by paths, they are linear elements that mark a transition from one continuous area or condition to the next.

Areas of varying genius loci allow players to feel that the world has variety in the way that games with distinct level theme types.

From a production standpoint, edges can mark a change in art style.

- Quick transitions: the area you are entering is the site of an event, or if you are transitioning to the realm of a specific group.

- Gradual transitions: help build anticipation for reaching a new zone, also indicate that you are reaching a natural border between environment types.

Districts

district, sections of a city where the observer enters “inside of” and which have some identifying character.

Once past the edges, players find themselves within districts.

Beyond changes in style, districts in games differentiate themselves from one another with changes in gameplay: types of NPCs, enemies, events, or mini-games.

If sandbox worlds do not have distinct districts, or if districts do not have their own unique gameplay elements, sandbox worlds can feel empty.

WORKING WITH CAMERA VIEWS

This section discusses how camera placement offers different limitations and opportunities for how gamespace is viewed.

3D Views

First Person

Level designers have full use of many of the architectural concepts. Designers must use the most architectural tricks to capture players’ attention, as the player has control over where the camera is looking.

limitation:

- platform jumping

- melee combat

Third Person

- The same spatial opportunities as first-person games - the ability to create full 3D environments where lines of sight and other visual tricks can be used to direct player attention.

- Camera’s sense of perspective - changing viewing angle options

- Fixed-perspective games: greatly increase the dramatic effect of certain scenes, though often come at the cost of ease of control of the player character.

Additional opportunities

- platform jumping: shadows

- brawler-style melee combat

Limitation:

- aiming

2D Views

Different from 3D: showing the player things that are beyond the eyesight of the player character.

Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense in his films

Side-Scrolling Space

- some of the most spatially limiting level types, as there is not much one can design in the way of pathfinding.

- location in a side-scrolling level can also be difficult to track, especially in large open-world 2D games.

The simplicity of side scrollers makes them effective at teaching their own mechanics: put everything the player needs to know in a screenshot’s distance from his or her avatar.

“to the side” point of view

Side-scrolling games have their own visual level metrics: enemies and enemy projectiles should always leave enough time from when they enter the screen to when they reach the player such that the player has a chance to see and avoid them.

Shantae: Risky’s Revenge: move between layers - x, y axes, also z.

Top-Down Space

Share the potential for Hitchcock-style suspense.

Axonometric / Isometric Views

Character’s relation to the environment around them.

ENEMIES AS ALTERNATIVE ARCHITECTURE

Enemies offer level designers a unique type of architectural ally in their antagonistic relationship with the player. Enemies block spaces by threatening to damage the player.

Half-life 2: alien soldiers at the beginning Fallout: New Vegas: high level enemies as obstacles

Functions:

- direct player movement

- make the scene populated - the role of architectural allies

- paired with narrow spaces: forcing player to take risks to past or combat

- swarm enemies to force player to run

SUMMARY

- From micro-scaled articulations of additive and subtractive space to world structures

- How to cater gamespace to the kinds of gameplay experiences we wish them to house through spatial size types

- Utilize molecule and proximity diagrams to pace these elements out or study how they interact with one another

- Organize large worlds of gameplay through urban design principles

- Cater player experiences of our gamespaces to the point of view they will have through in-game cameras

- Use not only friendly NPCs, but also enemies to populate our game worlds, enhance the spatial types we have discussed, and direct player action